I’ve been doing some statistical research on how the doctrine of foreign equivalents affects non-U.S.-based companies that want to use their brands in the U.S.

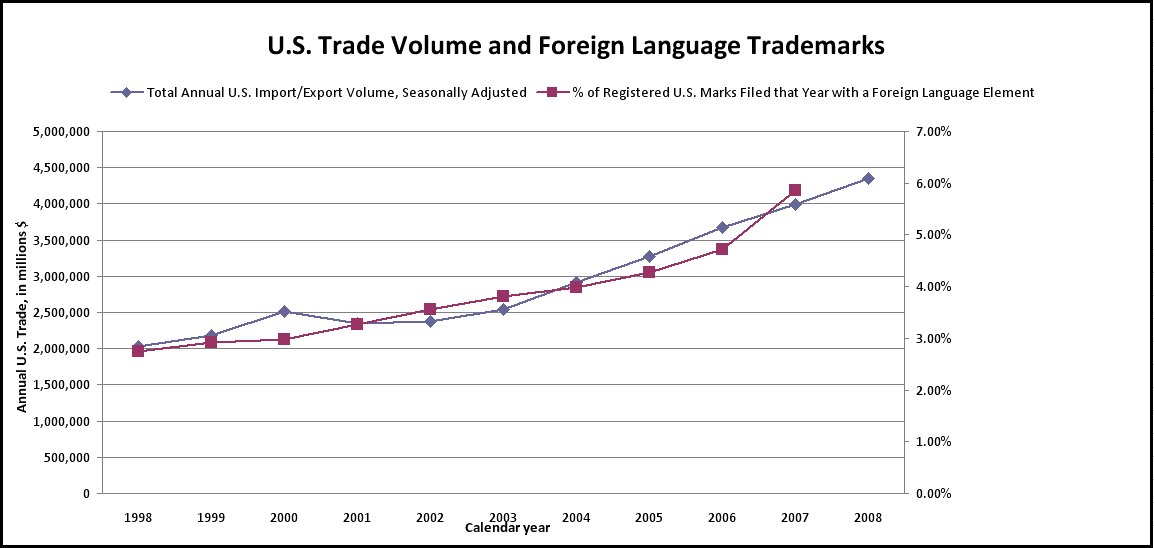

An interesting result of my research is this finding: The number of U.S. trademark applications that contain non-English words closely tracks the total volume of U.S. trade with other countries. (See the chart below.)

As background, it helps to understand that the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) considers foreign language terms to be equivalent to their English language translations when it reviewed trademark applications. This is true for evaluating both descriptiveness and confusion.

For example, the Trademark Trial and Appeals Board (TTAB) cancelled the mark AZUCAR MORENA (which can be translated from Spanish as “brown sugar”) on the basis that it was merely descriptive for the goods “unrefined sugar; brown sugar; molasses.” See Marquez Brothers International, Inc. v. Zucrum Foods, L.L.C., Cancellation No. 92048266 (December 11, 2009) [not precedential], available at http://ttabvue.uspto.gov/ttabvue/ttabvue-92048266-CAN-52.pdf.

In another case, the TTAB refused to register the mark LA PEREGRINA (which can be translated from Spanish as “the Pilgrim”) for jewelry, because there was a pre-existing registration for the mark PILGRIM, also for jewelry. See In re La Peregrina Limited, 86 USPQ2d 1645 (TTAB 2008) [precedential], available at http://ttabvue.uspto.gov/ttabvue/ttabvue-78676199-EXA-14.pdf.

This practice of translating non-English terms for comparing trademarks is called the trademark Doctrine of Foreign Equivalents. For the USPTO to implement this legal doctrine, it needs to know what foreign terms in trademark applications translate to. These translations become part of the applications and the eventual trademark registrations.

In the chart below, the left axis show the sum total of U.S. international trade (imports and exports are added together). The right axis shows the percentage of U.S. trademark applications that include a foreign language element by searching on the [TI] field of all trademark applications field in each calendar year.

The totals include some instances where the “Translation” field of the trademark application merely says that a word doesn’t have a meaning in a foreign language. But even this may be an indication that the application was filed by a non-U.S.-based entity, or that the trademark examiners at the USPTO are becoming more sensitized to the possibility of words having a meaning in a foreign language, and so are requiring this piece of information from trademark applicants.

Maybe these results are obvious: More international trade means more trademarks that have non-English components. But I still find it interesting to see how closely the graph tracks, across a total (from 2001-2008) of nearly 2.8 million trademark applications.

What consequences do you see arising from this bit of data?

Stay tuned for more results from my research in this area. And if you’d like to see more of the search details and research behind this, drop me a line.